Scamming The Scammers: How To Deal With Ambiguous Spam

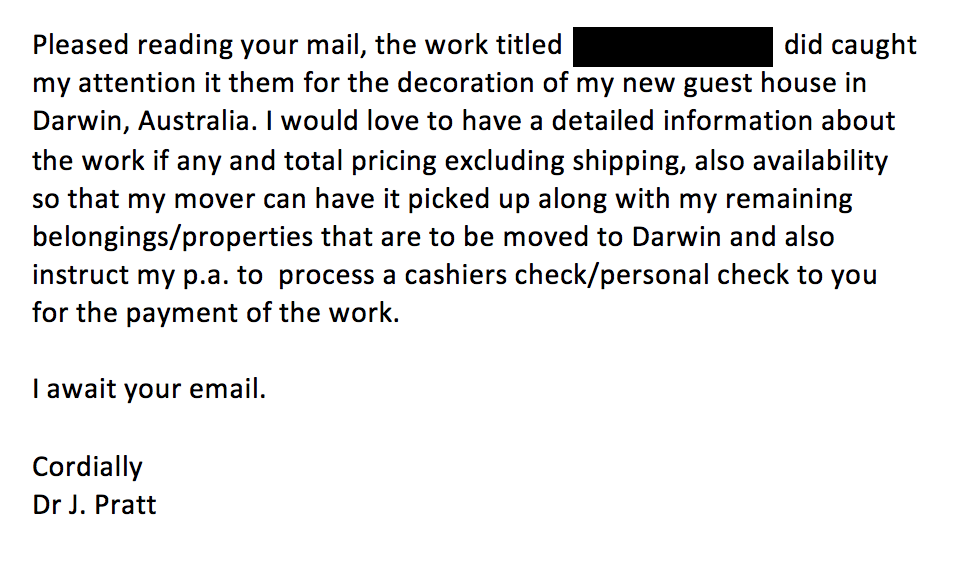

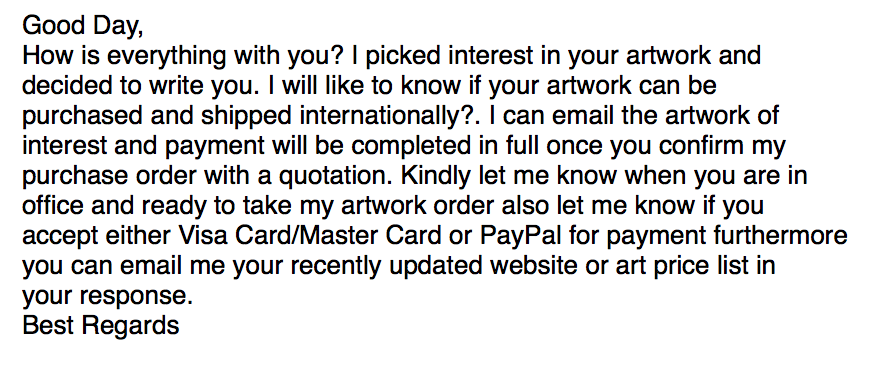

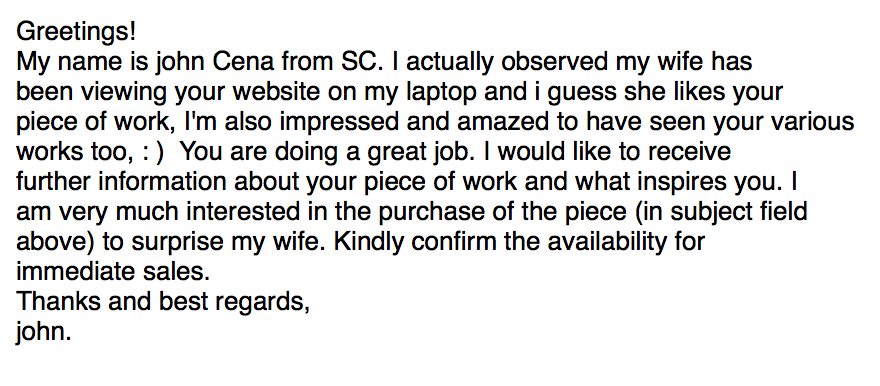

/My friend Adam is a professional illustrator and has been fending off spam emails like these for most of his professional life:

Now these are obviously scams, and like most of us Adam typically deletes them or sends them to his junk mail folder. But lately they've been getting more sophisticated and harder to spot, and Adam is concerned that more artists like himself may fall for them. Is there anything we can do to fight back?

I don't know how many artists fall for these types of schemes; I like to think most people are savvy enough to see through phishing attempts like this. But if the scams are getting better, they're more likely to convince someone to give up sensitive personal data. In today's political climate no one is looking out for artists. There’s a patchwork of federal and state laws such as the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 that ostensibly address commercial spam, unlawful solicitation, pornography, and various forms of computer crimes, but these laws are incomplete and often ineffective. The CAN-SPAM Act, which prohibits many types of commercial spam (but permits many others) itself has largely gone unenforced.

So if you wanted to take matters into your own hands, how could you do it? You could:

Report the spammers to a law enforcement agency;

Contact Anonymous or other white hat hacking groups;

Sue them if you can figure out who they are; or

Meet the scammers on their home turf and spam 'em right back.

Any of these options would feel satisfying. Turning the tables on your opponent usually is. But without money, time, or cyber-security know-how, most of these probably aren't all that realistic. And as for law enforcement, well as I said above, there's not much incentive these days to pursue Nigerian Prince-like schemes. There's another problem too. These spammers are a dime a dozen. Even if you successfully take one out, several more will spring up like a hydra. And let's not forget that many of them are attacking you from countries like Russia, China, and North Korea. Not exactly places where the U.S. has political capital.

The reality is that the best tool for fighting back against unwanted spam is education. It’s banal and not very satisfying for the vengeance-minded, but it does work… kind of how like comprehensive sex education contributes to lower teen pregnancy rates. So if one of these emails makes it through your spam filter and into your inbox, what should you look out for?

Poor Grammar and Spelling. Not every prospective buyer writes English well, but the wonky grammar in these emails tend to be a dead giveaway that you’re reading something written by a bot and not a person. Some of these emails can be well-written though, so be extra vigilant about that.

Lack of Specificity. Spam emails like the ones above tend to have few details about the buyer and demonstrate little or no knowledge of you and your work. You may get some generic compliments or odd bits of personal information designed to throw you off the scent, like “I saw my wife looking at your website” or “I’m moving to Australia.” But spam tends to largely be devoid of specificity and humanity.

Lack of Common Sense. These emails tend to ask for information that is easily and readily available and takes little common sense to find. As you can see, all three emails above ask Adam for information about purchasing his art... information that’s available on his website, which is easily Googleable. If this person had done enough investigating to find his email address, they certainly would have found his website. Oftentimes, they’ll offer to buy a work without asking the price or how to properly ship the work.

Bad or Incomplete Contact Information. Spam and phishing emails often give strange looking or contradictory email addresses. They rarely provide mailing addresses or phone numbers. In the event they do, the address is often an international one and/or improperly organized (like forgetting to put a state or zip code) and the phone numbers often have an incorrect number of digits or are international numbers.

Questionable Payment Options. Spammers are usually trying to get personal identifying information or access to your bank or credit accounts. They may ask for your PayPal account or bank information. Periodically, as in the emails above, they’ll offer personal checks or cashiers checks. The offer of a cashiers or bank check is especially curious as those checks are conventionally understood to be backed by a bank. If it’s a bank you’ve never heard of, do some research and find out if it’s legit.

There are some other things you can look out for as well. It should be said that even if the email contains some of these issues, the buyer could be real, so do some digging - find out who this person is - and use your common sense.

Under no circumstances should you EVER ship the work to the buyer until A) you’re confident it’s a real person and B) payment clears. And if there’s any doubt, just send it right into your junk mail folder and don’t give it a second thought. You’re too busy to spend your time trying to figure out if a buyer is a real person who wants to buy your work.